June 19, 2019

Don’t Design Learning Spaces, Design Learning Experiences

By Kelly Sanford

The traditional design process is broken. In a traditional process, leaders and users of an organization make a shopping list for what types of spaces they’ll need in a new building, let an architect design them with some input, have an A/V consultant try to fit the right technology within the space and budget, wait a few years for it to be built, and then figure out how they are going to fit their organization into the space and how they’re going to use and support the technology. Learning experience design is missing from this process.

In a predictable world, this traditional approach would have worked out just fine. For many years, there was a strong shared definition of a classroom: it was a place where a teacher stood in front of the room, writing on a board or projector, and students sat listening and taking notes. The classroom typically needed rows of desks, a lectern, and vertical surfaces for instructional materials (and a clock). New buildings could be designed based on simple capacity needs alone and architects could proceed by making assumptions from past projects: Dear Architect, please design me 14 additional classrooms and 10 new faculty offices of quality.

What’s Changing Today’s Learning Experiences

In today’s world, formulas from benchmarking and assumptions won’t do. Rather, you need to do the user research and design the future learning experiences – and use other valuable inputs to the design, like what makes your community unique, the activities of lead users, and your internal expertise (e.g., IT professionals, DEI advocates, or the Center for Teaching Innovation). This helps you identify and address change and uncertainty.

New technologies continuously change ideas about what’s possible and disrupt the status quo. Assumptions about what makes a good learning environment are being challenged, innovated, and tested with new tools and experimental pedagogies:

- How can the classroom be flipped so lectures are recorded in something like a one-button-studio and viewed in advance so that class time is spent solving problems together?

- How can student teams create things in real-time and share them with the rest of their class?

- How can presenters and participants join from other locations and see each other and content in real-time?

- How can the class switch seamlessly from lecture to small group discussion to debate?

- How can the creation and the conversation in the classroom be captured?

Learning Experience Design: A More Nimble Design Process

In this changing world we benefit from a more nimble design process; a process that invites conversation and creativity; a process that gives organizations an opportunity to holistically review and reflect on where they have been, where they are going, and what the future experience is that they aspire to create within the spaces they inhabit. One way to do this is to approach building design as part of a more holistic learning experience design process.

At brightspot, we think about people, programs, and places together in an experience design process that starts with understanding our users and progresses to prototyping experiences with them. Throughout this process, we return to the pillars of people, programs, and places. We have a tried and true set of tools to accomplish this work (We also have a set of experimental tools, but we haven’t finished prototyping them to share with you here!).

People: Researching Users and Developing Personas

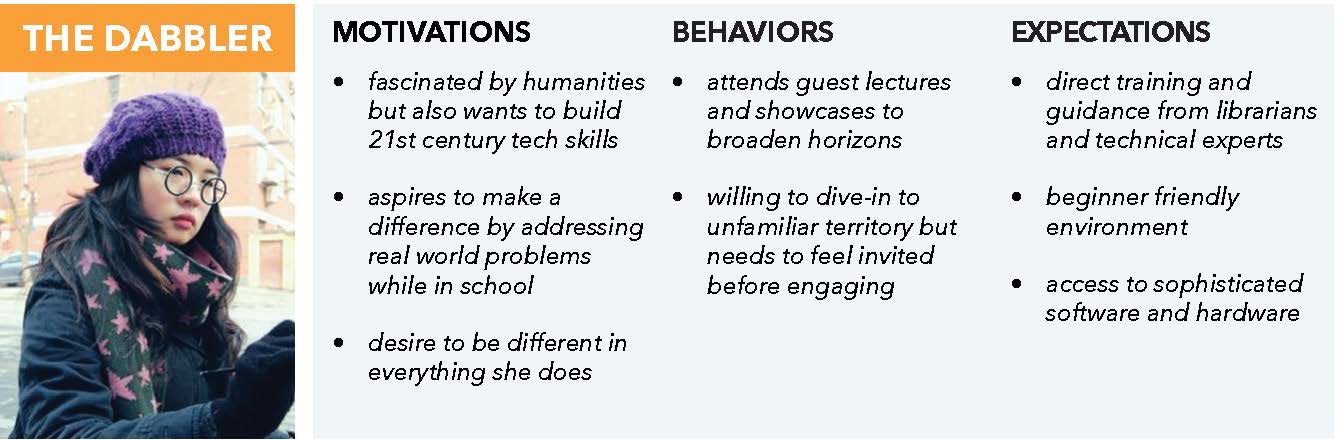

We start with people. Who are we likely to encounter during this experience? Who are we trying to engage? What are their motivations, behaviors, and expectations? What are the tools and technologies they’ll need? As a framework for this conversation, we build personas, which are fictional characterizations based on real users that serve to remind us that our users are not one block of “average people” but in fact a diverse set of individuals with different perceptions, desires, and unique challenges. We use personas throughout the process to inspire new ideas, quickly “gut check” (or evaluate) experiences as they come together, and remind ourselves who we are doing this work for in the end. As learning experience designers, one of our motivations is to create a better experience for our users, so it’s important for us to know them!

Below you can see an example of a student persona we created for a library experience design project.

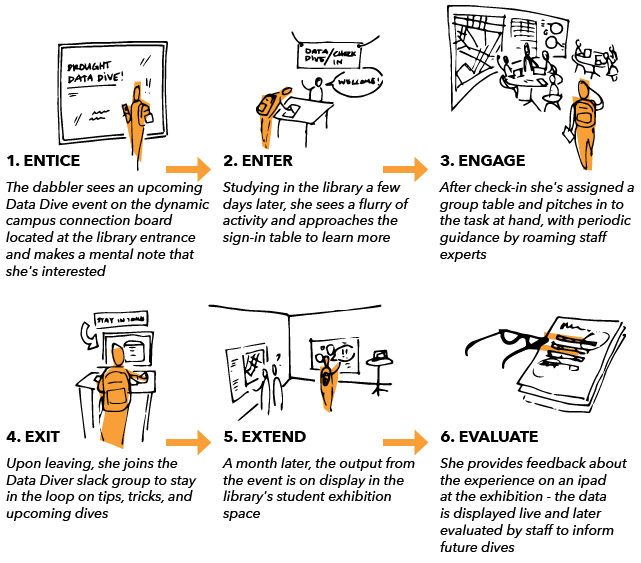

Programs: Mapping the User’s Journey

Once we have a good understanding of our user, we start creating a story about their engagement with our service or experience by using a Journey Map (sometimes referred to as an Experience Map). A Journey Map looks at the journey of the user through touchpoints over time. It represents an expanded view of the core experience by taking into account decisions made before and after the main event. To prevent ourselves from developing tunnel vision about the boundaries of the learning experience design, we use a framework called the 5 E’s which were originally developed by Conifer Research and extended by brightspot to include a 6th E. The E’s identify the different phases of the experience over time.

- Entice – How does the persona learn about the experience? What makes them decide to participate?

- Enter – How does a persona enter the experience? Do they need to sign in? Click something? Are they greeted or welcomed by someone?

- Engage – What is the experience? What is the core offering? What did the persona come here to do?

- Exit – How does your persona leave? Do they sign out? Do they get any collateral before they go?

- Extend – What keeps them coming back? Do they get a reminder for the next event? Does someone follow up with them about what they experienced?

- Evaluate – How can we get feedback from the persona? How might we engage them to continually improve on our offerings? What indicators are most important to track?

Once we have mapped the primary touch points, we can expand on the framework in a number of ways by adding additional rows to the sequence or tacking on sticky notes. Common “booster packs” to a simple Journey Map might include the following:

- What is the user thinking and feeling during this E?

- What technology is needed for this E?

- What spaces are needed to support this E?

Places: Supporting Experiences with Space and Technology

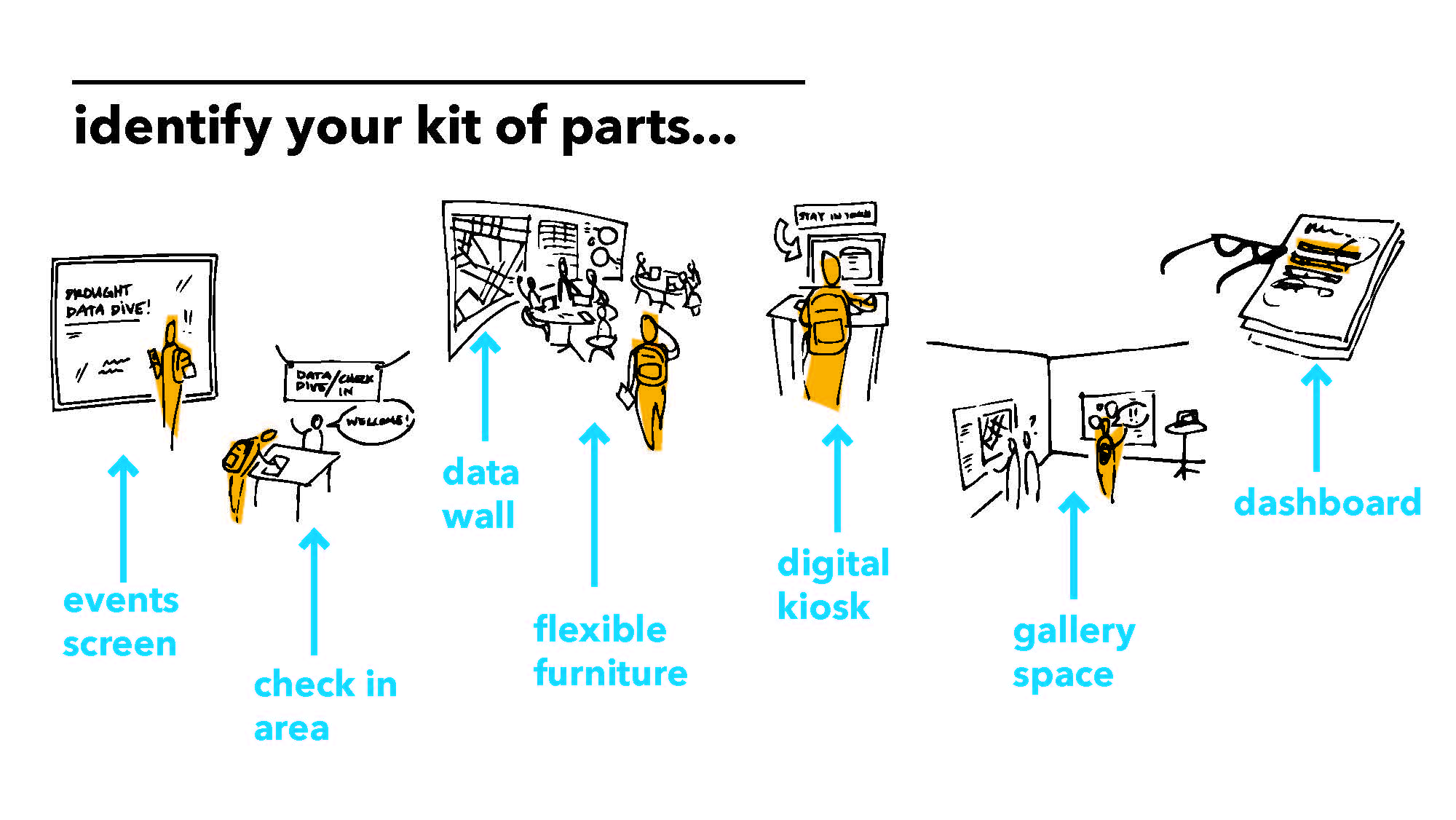

Once we have a strong sense of the persona and their journey, we start diving into the design of the spaces and technology to support and optimize this experience.

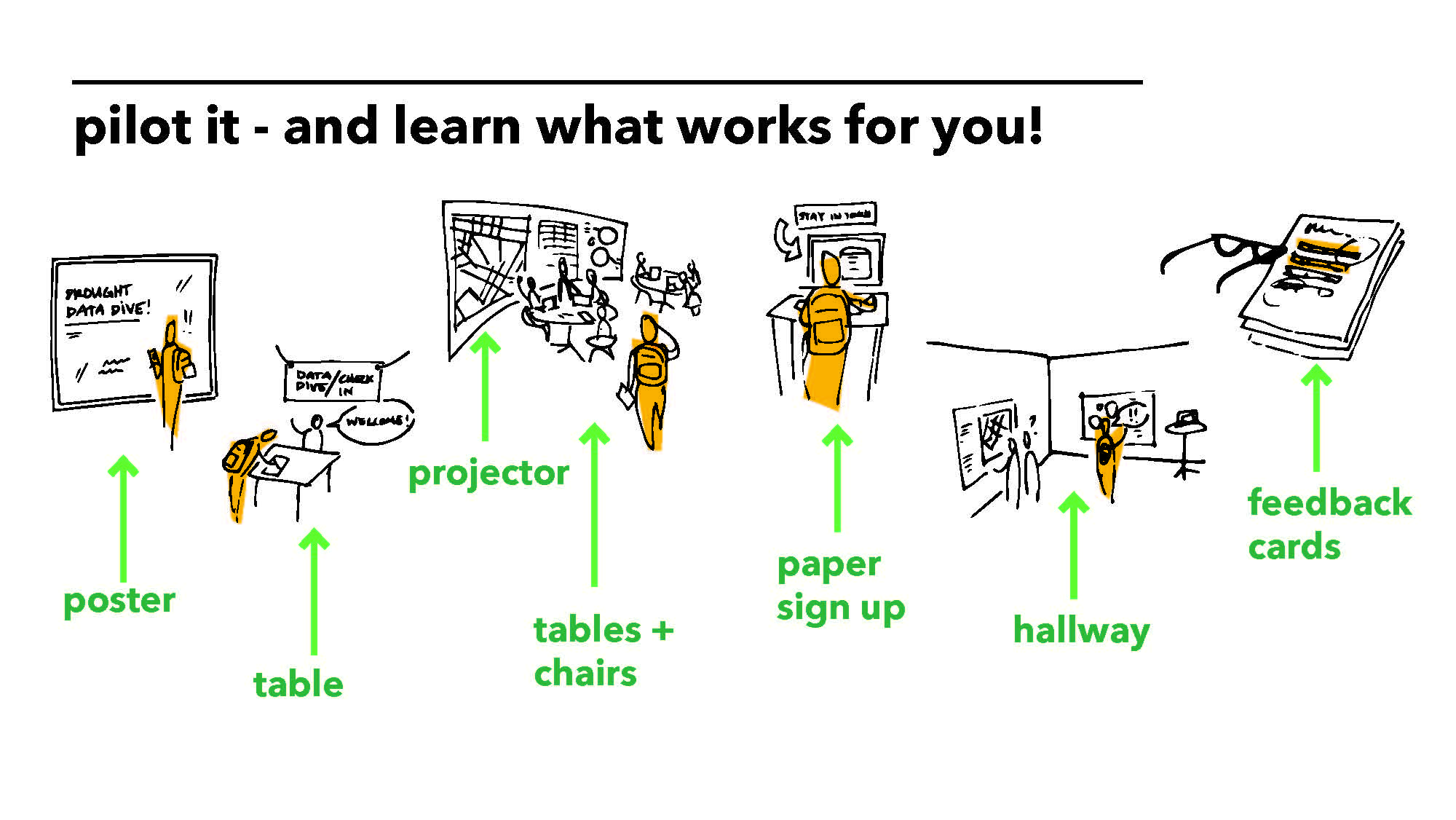

It’s tempting to jump straight to ordering equipment, drawing up plans, and finalizing decisions, but this is where we recommend you pause and test your idea with real users by prototyping the experience.

You will be making a big investment in your new space (and in training your team), and it’s worth the time and effort to make a small investment of time and money to get it right! It’s time to identify your kit of parts.

Think about the equipment and tools that you might need to support your experience. In the example below, the experience was a hackathon supported by a series of investments like an events screen, a check-in station, data visualization wall, flexible furniture, and digital kiosk. Though these are likely to enhance the experience in some way, the team can optimize what’s needed by putting on their MacGyver hats and running a prototype of the experience with resources that are readily available. For example, you may learn that a series of smaller monitors is more valuable than one extra large screen, or that participants are blasting past the check-in desk so approaching participants at the tables is more convenient and inviting. After testing your idea with a kit of parts, you will be able to communicate the core needs to experts who can help you generate the best possible space with the best possible technology to support the vision.

The benefits of approaching your project with a learning experience design framework go beyond creating a more effective space design. In our experience, we’ve found that the collaboration built into this process builds stronger relationships between staff and their partners, it helps ready organizations for change by involving people early, and produces cost savings while generating a strong story surrounding the project that serves to defend it from the value engineering knife. We hope you can put these tools to work for your next project, and we invite you to share the outcomes of your effort!

The benefits of approaching your project with a learning experience design framework go beyond creating a more effective space design. In our experience, we’ve found that the collaboration built into this process builds stronger relationships between staff and their partners, it helps ready organizations for change by involving people early, and produces cost savings while generating a strong story surrounding the project that serves to defend it from the value engineering knife. We hope you can put these tools to work for your next project, and we invite you to share the outcomes of your effort!