January 17, 2019

Organization Design for Higher Education Project Success

By Elliot Felix

A team is a group of people working toward a common goal. Now, imagine a sports team in which people don’t know one another, don’t know who’s playing what position, don’t know what the rules of the game are, haven’t practiced together, and don’t know how to win.

As crazy as this scenario sounds, it is not far off from how many project teams proceed at colleges and universities to rethink a program, redesign a service, renovate a space, or reorganize a department. Every day, faculty and staff are assembled to take on unfamiliar tasks in collaboration with colleagues and consultants who are new to them as well. Not enough thought goes into how to set them up for success.

A project committee is a kind of team, but too often these groups never become high-performing teams. Projects suffer as a result; deadlines are missed, budgets exceeded, people disengaged, and opportunities lost. It’s often assumed that new project teams will instantaneously be high-performing teams. Instead, academic leaders can be strategic in how they create project teams by thinking of this as an organizational design exercise.

A Better Way to Organize Projects and Teams

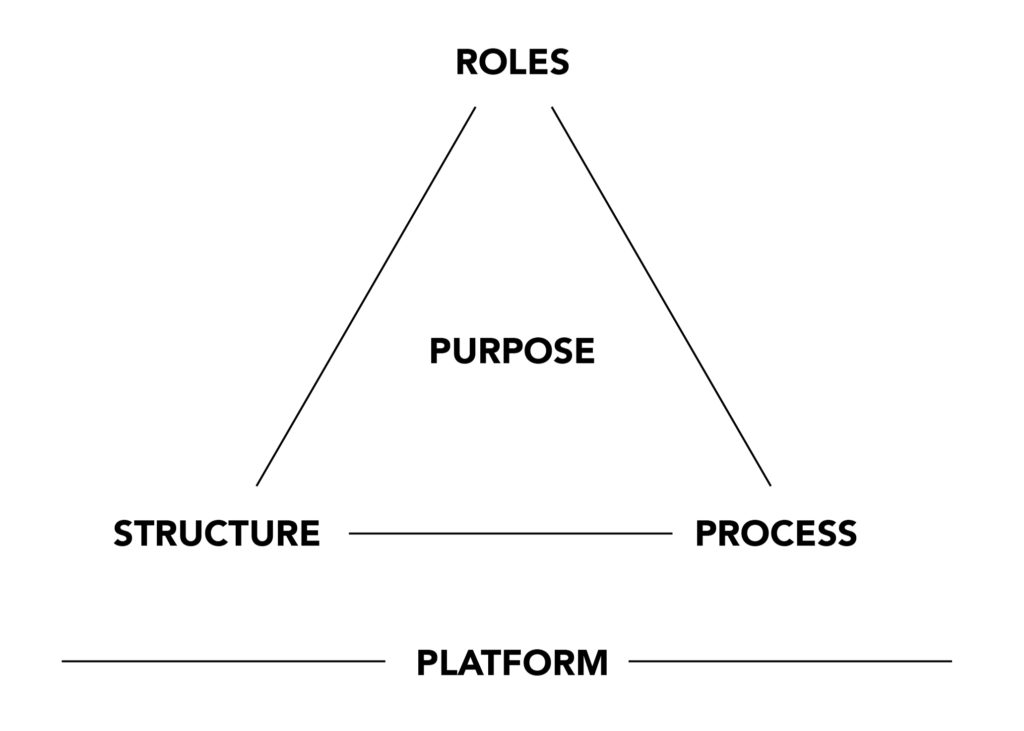

After 125+ projects with 75+ colleges and universities, and paying close attention to the success or failure of different projects, we’ve developed an approach to organizational design that institutions can use to set up project teams for success: consider the roles people play, the structure that connects those roles, and the processes used to fulfill the roles — all working together to achieve a purpose and supported by a platform of information, tools, and skills.

Defining Purpose

The purpose of the group should be concisely defined in a charter that plainly states what the group needs to accomplish, by when, why, what the desired impact is, and how achievement of that goal will be measured. This purpose should create a sense of urgency that they’re meeting for a reason, for a defined period of time. It must also make clear precisely what the team is empowered to do.

Creating the Roles

Roles on the team can be thought about in terms of representation, function, and perspective. For instance, a student experience transformation project might include admissions, financial aid, registration, advising, facilities, libraries, career services, and academic leadership. Functional roles determine who’s responsible for what tasks. Perspective makes sure you have a balanced group that represents different points of view; for instance, using frameworks like the Kantor-Isaacs “Four-Player Model,” where someone moves, someone opposes, someone follows, and someone bystands (aka “advises”).

Designing the Structure

The structure relates the roles. It should consider if there are any subgroups within the larger team and how they relate. It should clearly designate specific hierarchies. For instance, who is the chair/leader? Are there different tiers or types of team members such as advisory (i.e. non-voting) members with different responsibilities? The structure should also make it clear if and how people can play multiple roles and how roles can change. Like an org chart, it ought to be written in pencil because it will need to adapt to what the team is learning.

Facilitating the Process

Project committees typically suffer most in terms of process. First define how, when, and where the team will meet, work, and communicate. Next, define how the team will make decisions. Will it be by consensus? By voting and, if so, by simple majority? By consenting to the leader’s decision once people have been heard? Then, people must have different ways to participate because people think and work differently.

Supporting with a Platform

Even the best team needs the right platform of information and tools supporting it to succeed. All the team’s information needs to be in a shared place; people can’t be hunting through their email to find a specific document. Team members should create other basic tools like a shared distribution list, a shared calendar with milestones and meetings, and a library with shared resources. Shared experience is also foundational; for instance, a trip to study peer institutions provides time to bond and shared references that facilitate collaboration.

With a little bit of preparation, leaders can create high-performing project teams and position them for success. Being intentional about the purpose of the group, the roles people play, the structure that relates these roles, the processes they use, and the platform that supports them will pay off and create a winning project team.