August 7, 2019

Making Space for Online Learning

By Elliot Felix

It’s a misconception to think that colleges and universities can grow enrollment by offering high-touch online programs without changing their physical facilities. While the growth of online education can significantly bring down overhead and maintenance costs,1 campuses need to make physical space for online education.

Courses have to be designed, developed, and taught. Students have to be recruited, enrolled, supported, and placed in the workforce. Institutions have to make space for online learning: spaces to welcome students, spaces to design and develop courses, spaces for students to connect in, and spaces for staff to support students from.

The online and on-campus worlds are converging: institutions are flipping the classroom to put lectures online and use class time for discussions and problem solving; online students increasingly enroll close to home (67% within 50 miles!); and the nearly two-thirds come to campus at some point by choice or for a required immersion event.

In this post, we look at who’s studying online, how colleges and universities are making space for their online programs, and how you can plan ahead so that you can make the most of your investments in space, technology, services, and people.

Who’s Studying Online, Why, and How?

Using the latest data from the National Center for Education Statistics, we know that 33% of students in the US today take at least one online course, with 15% fully-online and 18% taking a combination of on-campus and online courses. The compound annual growth rate for online enrollment is 10%. The average online bachelor’s student is 32 years old, 95% are returning to school, 84% are employed during school, and as of 2017 bachelor’s students outnumber online graduate students 5 to 1.

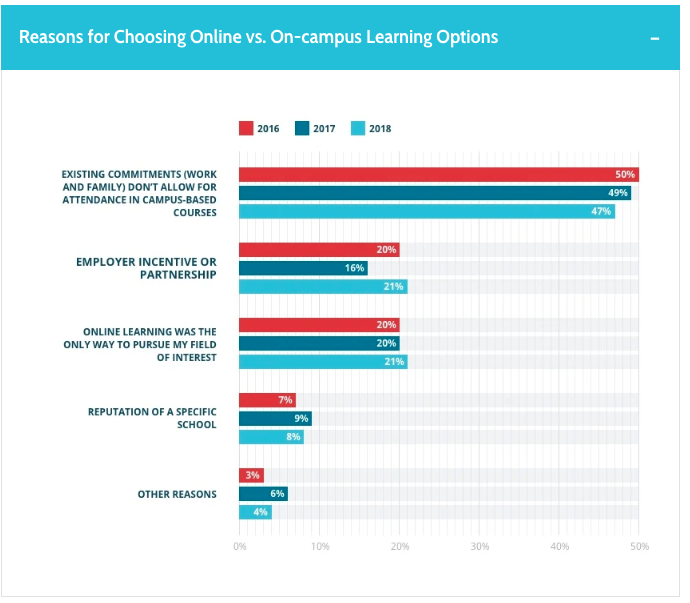

Considering online students overall, 69% are career-driven – either trying to start a career, accelerate their career, or switch industries. Upon reflection, their career focus is further amplified: when asked what they’d do differently, students’ top choices are speaking to employers/professionals in the field and speaking with alumni (both cited by 21% of students). Flexibility and convenience are the primary reasons for studying online, and students report 60% of their communication is synchronous and 40% is asynchronous.

Growth in Online Education: Who’s Providing Programs?

Institutions offering online programs do so for a variety of reasons: to meet student demand (72%), as an opportunity to grow enrollment (71%), to leverage something they already offer on-campus (66%), to meet employer demand for knowledge/skills (59%), or tap existing expertise in an area (44%). Of these institutions, 68% are public, 18% are private non-profit, and 14% are private for-profits. Examples include individual colleges and universities, “mega-universities” like Southern New Hampshire University or Western Governors University, a consortia of public institutions within a state system, or a consortia of private non-profit institutions such as through the Council of Independent Colleges.

Why are Colleges and Universities Making Space for Online Education?

First, let’s state the obvious: online students and faculty have bodies (at least for the moment), and so those bodies need a physical space to think, write, listen, talk, code, design, and build in. So, “fully-online” is something of a misnomer; some space is involved, even if much of the work happens on a mobile device and many support functions are handled by an outside online program manager (OPM) like Noodle Partners.

Online students take up space – at home, at work, in coffee shops, and on campus when they periodically visit. Faculty and staff take up office space because courses have to be designed, developed, and taught, while students have to be recruited, enrolled, supported, and placed. As students continue to enroll closer to home and some face-to-face residency or immersion component is included, this need for space will continue.

Online students take up space – at home, at work, in coffee shops, and on campus when they periodically visit. As students continue to enroll closer to home and some face-to-face residency or immersion component is included, this will continue. Faculty and staff take up office space because courses have to be designed, developed, and taught and students have to be recruited, enrolled, supported, and placed.

Growth in Online Education: What are the Spaces Needed?

Institutions have to make space for online learning: spaces to welcome students, spaces to design and develop courses, spaces for students to connect in, and spaces to support students from. Let’s review these individually, thinking roughly in terms of the student experience lifecycle:

- Spaces for welcoming: Many institutions have designed a campus tour of sorts by creating an admissions welcome center that functions like a briefing center; this allows prospects to attend presentations, walk through exhibits, and meet with admissions counselors to understand the institution and its programs (and briefing centers are a discipline unto themselves; there’s even a professional association for them, the ABPM).

- Spaces for course design and development: While some courses can be designed and developed by an individual faculty member with not much more than slides, a microphone, worksheets, a webcam, and the existing LMS, many courses require more design, higher-quality media production, and technology support (which also increases course quality2). Ideally, faculty have one place to go for instructional design, interactive development, media production, and assessment, like UC Berkeley’s Academic Innovation Studio.

- Spaces that complement the online experience: Education is social and relies on the right set of support services. These services might include required immersion for a weekend on campus, visiting companies, or attending a conference. It might be meetings between students to connect in a social setting or to work on projects, attend an event, or even watch a recorded lecture (and pause and discuss them in real-time). It might be a face-to-face meeting with a professor visiting the area, a local alum, or a career advisor. So even the best online learning platform can be complemented by physical spaces, and universities can use their existing campuses for these (if it can accommodate the increased demand), they can use shared workspaces, or it may mean creating a new storefront “microcampus” as a satellite for a suburban institution reaching an urban student population.

- Spaces for blended courses: While we’ve established “fully-online” is a misnomer, many on-campus courses intentionally blend online and face-to-face modes of learning. The most popular example of this is the “flipped classroom” in which recorded lectures and readings are put online and completed before class so that class time can focus on interactive learning modes like discussions and problem-solving in real-time when the instructor is available to guide and advise. Blended classes have four major space impacts: they reduce the need for traditional lecture halls; increase the need for media recording/production spaces like one-button-studios; make classrooms flatter, more flexible, and larger space per seat; and increase the need for collaborative project space within libraries and elsewhere on campus.

- Spaces for supporting students: It’s tempting to think your institution can do more with less to accommodate the increased enrollment from online students without adding faculty and staff. But increased course loads can mean increased faculty. It may be the case at some colleges and universities where there is latent capacity to be tapped, but many should plan on adding headcount or working with an external partner (like an OPM), or a combination of the two. Course design and development requires instructional designers, interactive developers, and videographers. Technology requires support. Students and faculty need support from library professionals on papers and projects. So, there is likely an incremental add to workspace for all these staff – and these staff are likely to be working more flexibly to support students at different times and in different places. As the needs of faculty and staff change, the academic workplace needs to evolve to meet these needs.

How to Make Space for Online Education

As we’ve seen, online education takes up physical space. Courses have to be designed, developed, and taught. Students have to be recruited, enrolled, supported, and placed. Institutions have to make space for online learning: spaces to welcome students, spaces to design and develop courses, spaces for students to connect in, and spaces to support students from. To move ahead, we recommend that institutions:

- Assess their current capacities in terms of faculty, staff, and space (i.e., classrooms, libraries, and office space), identify gaps or surpluses, and determine some useful planning ratios like “courses per instructional designer.”

- Survey the competitive landscape to see what peer institutions provide. What programs, policies, and processes do they have in place for online students to use the campus? Do they have a micro-campus? Do they have partnerships with coworking companies for drop-in workspace?

- Forecast future needs using enrollment numbers and course numbers times some capacity rules of thumb from your assessment; for instance, future courses x IDs/course = future ID headcount. Then, this headcount planning can be translated into workspace needs.

- Get creative to meet these needs so you’re using space as efficiently and effectively as possible. A micro-campus could be shared with a company who needs workspace during the day but not in the evening. When it comes to media production, think “minimum viable studio”: don’t go for top production value if a self-serve one-button-studio will work. To accommodate additional staff, consider a flexible, activity-based workplace that can more easily accommodate headcounts in flux. To create one-stop-shop course design and development support for faculty, consider locating it in the library or another central place to achieve economies of scale instead of each school having its own.

- Assess and learn as you go. Online learning is still in its infancy compared to on-campus instruction and the convergence of the two is in its early stages as well. It’s best to regularly assess utilization, satisfaction, and outcomes and then adjust as you go.

If this seems like a daunting task, it need not be. Scale it down to a manageable unit; if not the college, then the program. If not the program, then the course. Then, once you’ve determined what your online space needs are, you can extrapolate and adjust.

You can learn more about how brightspot enables online learning in collaboration with Noodle Partners here and good luck as you move ahead!

Endnotes:

Endnote 1 Online programs can certainly reduce costs (and some states like Florida have required state institutions to charge less than on-campus programs), but the costs of online programs vary widely. This is particularly affected by course size and the degree of student-faculty interaction. For instance, in one survey all 197 institutions surveyed by 2017 WICHE report that interactive online learning costs the same or more than face-to-face.

Endnote 2 The Changing Landscape of Online Education (CHLOE) 2019 Report by Report Quality Matters and EduVentures Research demonstrated that when faculty work on their own, 64% of student engagement is with course materials whereas when faculty are required to work with an instructional designer, that drops to 47% and interaction with peers and instructors increases.